The last stragglers of the spiderflowers, butterfly bush, and heritage flowers lost the fight two nights ago when we had a hard freeze. First night down to 28F killed off the garden for the year. I’ll have to go dig up the canna lilies and dahlia bulbs real soon.

The only thing that appears to not have been taken by the freezing weather is the celery and it still looks remarkably alive. Oh yeah, some lettuce is still growing green. It was re-seeded from previous lettuce plants that were allowed to flower. One kind in particular, an Austrian heirloom type of Romaine lettuce, called “Freckles”, has re-seeded like crazy.

It’s so sad to say goodbye to the summer tomatoes and peppers and basil!

We harvested the garden onions a couple weeks ago. We knew it was time to harvest the onions as the green shoots had pretty much turned brown and had flopped over onto the ground. It was obvious that they weren’t growing any more.

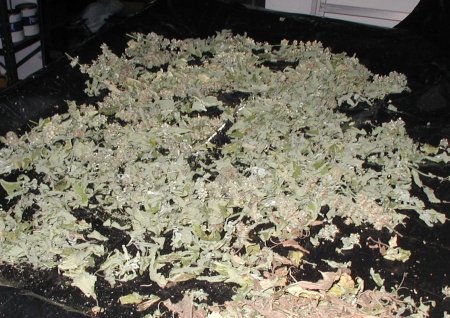

The onions were pulled up and the shoots were cut off a couple inches above the bulbs. Any excess dirt clinging to the roots was brushed off and the onions were laid out on a plastic sheet. The onions were positioned so that none were touching each other and they were allowed to dry for a long week. The sweet Walla Walla onions will be used in the kitchen over the next couple of months.

Freshly harvested Walla Walla onions from the vegetable garden. Photo taken on 11OCT08.

Walla Walla Onions were put in the garden as small onions, 1/8 inch in diameter, in late May. We purchased two 6-inch square flats with three rows of the baby onions that numbered approximately 4 dozen per flat. Some onions were eaten as ‘green-tails’ during the summer and we still harvested 50+ small to medium onions.

Dried onion weight is estimated at 5 pounds – at least. We paid only $1.30 for each flat of onions – each producing a row of onions when planted a few inches apart. The ones that were planted too close together were simply eaten first.

For every dollar spent on onion input, we got back at least two dollars worth of onions at the end of the growing season. Seeing that we ate a few of the onions as they grew the benefit was higher than doubling our money, probably closer to tripling our investment. Not that I want to become an onion farmer, but isn’t it nice that we’ve actually gained something in addition to the time spent outdoors?

Let’s see what our return on investment (ROI) was for growing Walla Walla Onions. ROI is calculated by dividing the profit by the total investment and expressing the result as a percentage.

ROI (%) = ( Profit / Investment ) x 100%

For example, our outlay of money was $2.60 to purchase the onions. Since we’ve obtained other benefits for the time and labor spent on planting the onions, tending the onions as they grew and harvesting them, we’ll say our total investment was only $2.60.

Purchasing sweet onions at the grocery store will set you back $1.69 per pound when they’re on sale, or $1.99 per pound at regular price. For a nice round figure, let’s say our harvest was 5 pounds of onions at a value of $8.45 to $9.95, depending on whether you use the sale or regular price of onions. How much are you paying for onions these days?

Profit is figured as the value of the harvest minus the investment, or $(8.45 – 2.60) = $5.85 to $(9.95 -2.60) = $7.35.

ROI ranges from (5.85/2.60) x 100% = 225% to (7.35/2.60) x 100% = 283%. So, on average, we can say that our ROI for growing onions was 250%. If you can get any other investment to give you such returns, you’re probably doing something illegal!

Ok, so we’re not dealing with great big numbers here, but I did get the validation I was looking for. I wanted to know, “Is my time spent gardening going to benefit my pocketbook as much as my mind and body?” The answer is obviously, YES, it is.

It feels really good to eat food that we’ve produced. It feels fantastic to avoid paying the high supermarket prices of today. For a few months I can pass by the onions at the grocer with a big smile on my face knowing that we’re stocked up on our onions.

You may be asking, “But what about the investment of time, labor and fertilizer and such?” I think I hoed the onions only twice this growing season and I may have pulled a few weeds in between hoeings. No fertilizer was used, so there was no other money input. Time spent preparing the soil in the beginning of the growing season can be spread across all the crops.

It’s good activity to keep us young, so the time spent gardening is not considered a cost in growing our vegetables. I’d much rather stay at home and pull a few weeds than drive half an hour to the grocery and give my money to someone far removed from the farmer for food that may have been grown in a far away land!

I’m hoping that more people will return to such wholesome ways as creating a Victory Garden at home. It’s not difficult to do, and actually, vegetable gardening can be very rewarding, and delicious, too!